Week 4

Updated 2022-02-01

What happens in memory when we run a program and where does the varaibles and data go?

Stack and Heap

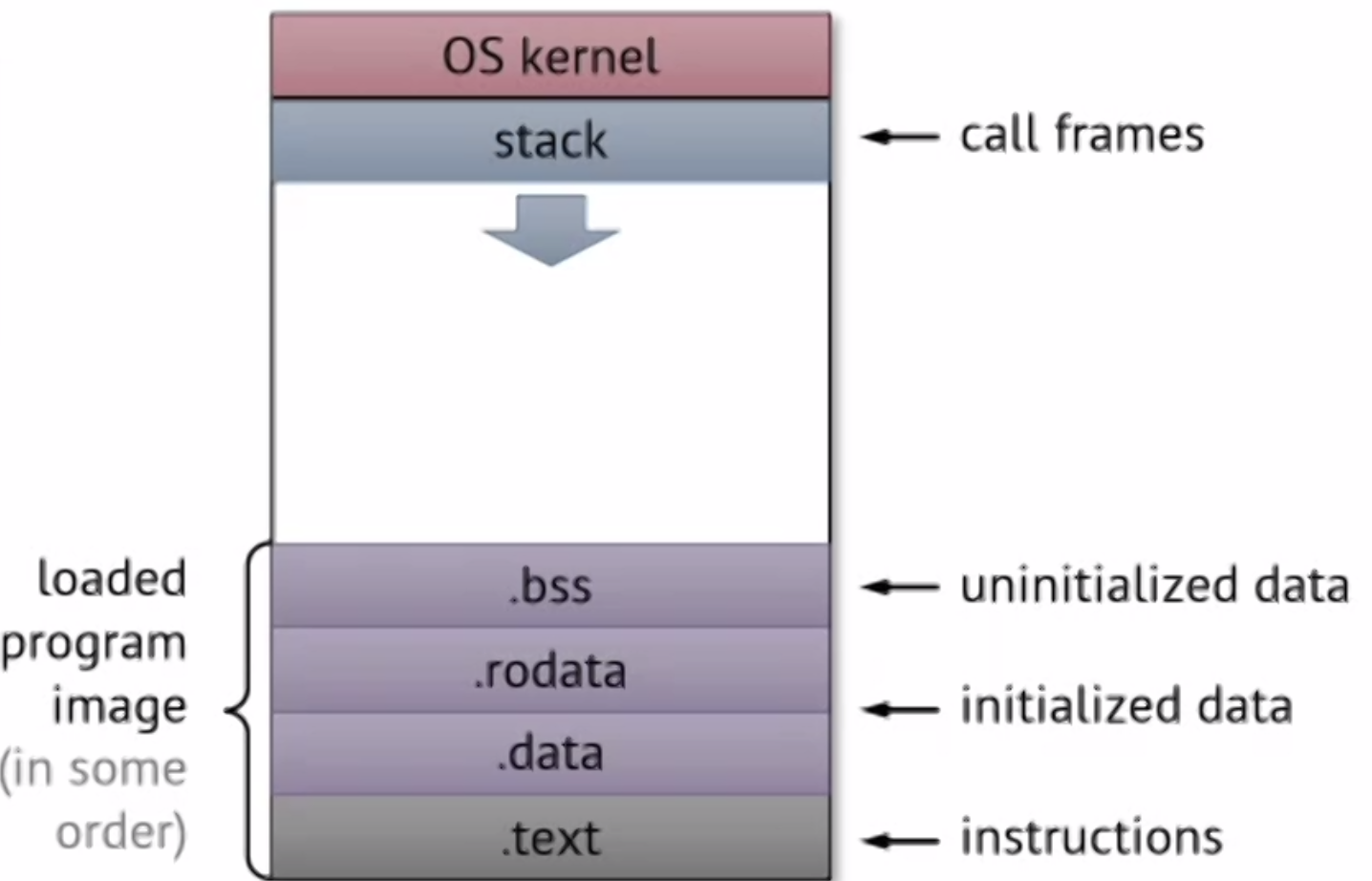

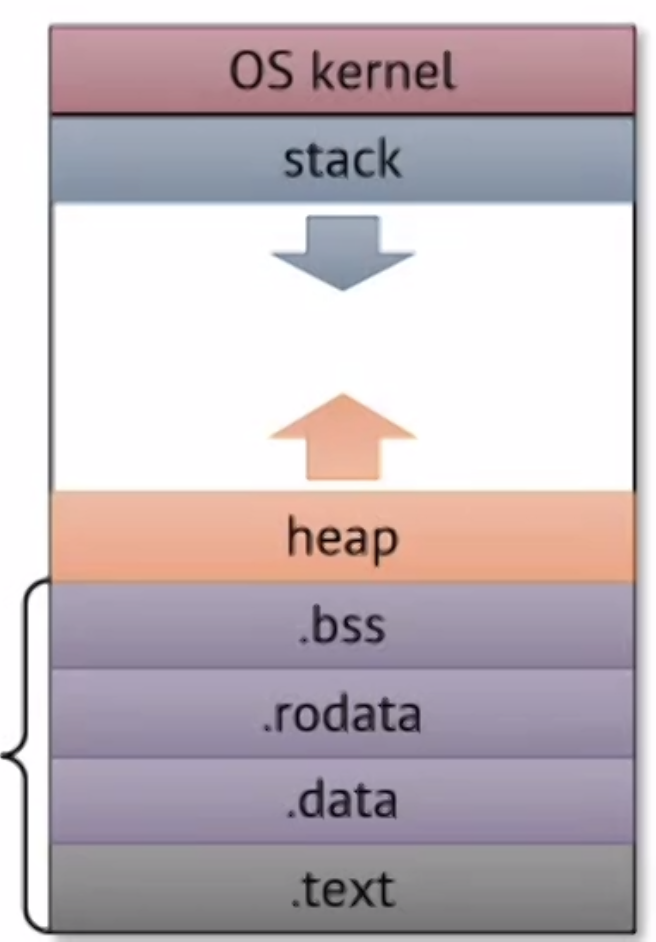

For each program, there is the same address range in the address space. and layout for each program – this is possible using virtual memory (later in course).

We already knows about the stack, and we know stack grows down (in memory addresses in the address space). The stack holds the call frames and its local variables.

But there are some more initialization stuff at the end of the address space. When a program gets loaded from disk, this is what is allocated.

For other storage, they’re placed on the heap, which starts at the end (before .bss) and it grows back up.

Typically the address space is large enough such that the heap and the stack don’t collide. There are other protections to keep it from happening – such as a stack allocation limit.

Unlike stacks, things allocated on the heap survives function calls, but things allocated on the heap must be allocated and managed more deliberately.

Managing Allocation

-

Manual allocation: using

malloc()andfree()function in C, andnewanddeletein C++. These allocation and deallocation operations must be done in pairs or there might be memory leaks.This is straight-forward but is hard and buggy to use – e.g. how do we know if something is safe to be deallocated?

-

Automatic allocation: just allocate and forget it. Then there is some mechanism like garbage collection and referencing counting to keep track of what to deallocate. E.g. Java uses garbage collection so things that programmers don’t need to worry about allocated objects.

Implementation is complex but is very easy to use by the programmer.

In C, we do manual allocation using

mallocandfreefunctions.

Heap Allocation Constraints

Before we look at how allocate/free mechanisms work, we have to consider things to make memory highly utilized:

- There is only limited physical memory / capacity for all programs

- The OS only gives blocks/chunks of memory (usually 4 KB pages) upon memory allocation – no matter how small. (If you have some code that allocates for just one byte, 4 KB of physical memory is going to be used up, as you’re only using a tiny bit of a page — low actual utilization).

We also want fast allocation of memory, so we also need to consider:

- The management overhead for allocating must be small, since memory-intensive applications would suffer greatly.

😭 Unfortunately, it’s very hard to get both high utilization and low overhead.

Simple Allocator

Let’s build a naive heap allocator based on how the stack allocates, recall allocating on the stack:

- Increment stack pointer to allocate

- Decrement stack pointer to deallocate

- Data addresses can be found by +/- from stack pointer/frame pointer

The stack allocator is nice because it’s easy to manage and easy to implement.

However, to understand why this is “naive”, let’s go through an example. In this example, we will allocate and free addresses in this sequence:

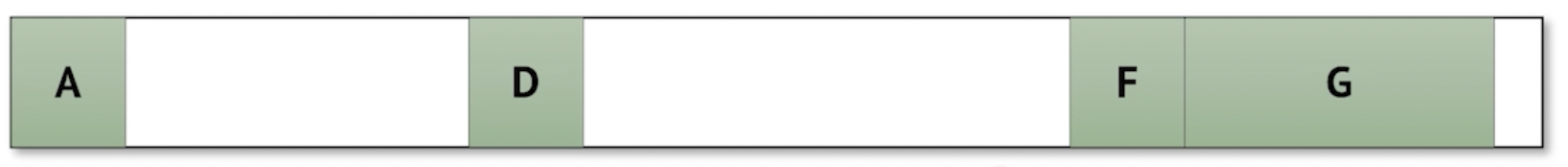

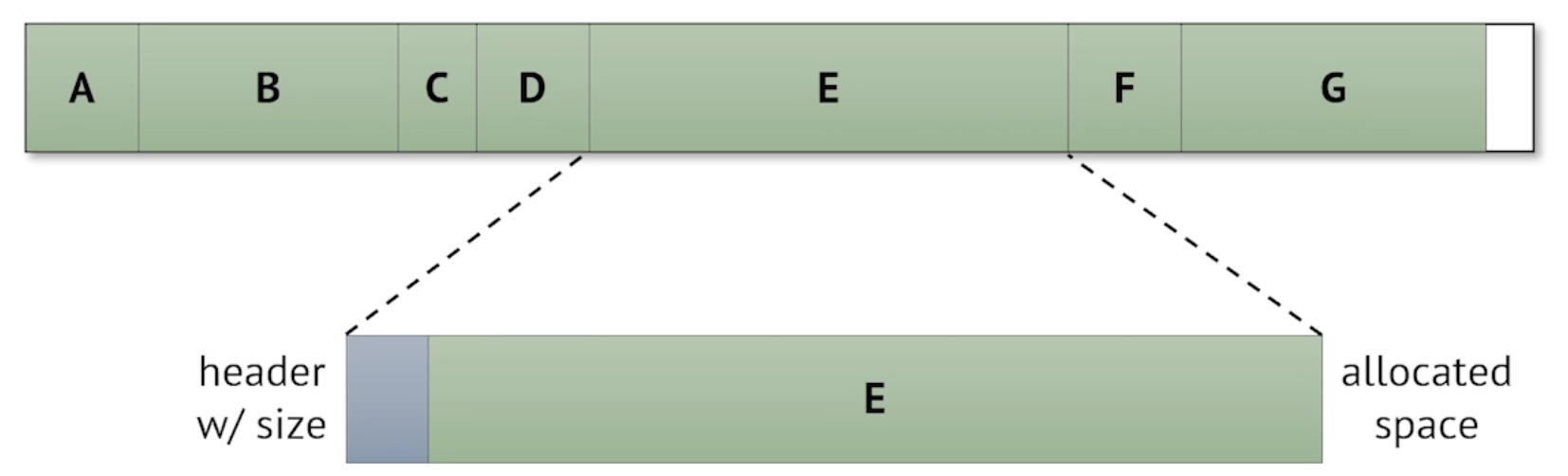

allocate A

allocate B

allocate C

allocate D

allocate E

free C

allocate F

free E

free B

allocate G

allocate H ⚠️

Suppose that after we allocate G, our physical memory for the heap has been completely used up:

The empty spaces between A, D, and F are from freeing the addresses B, C, and E. Despite the low occupancy, because of how our naive allocator is designed (to push new allocations to the end), we cannot allocate H beacuse there is no more free space at the end.

This phenomenom is called fragmentation since allocated areas are fragmented. We can improve utilization by reducing fragmentation, but to do so we need to:

- somehow track the block size

- given some free spaces, somehow find which free space to use when allocating small blocks, and find ways to utilize remaining free space.

- somehow track when and where blocks are freed; and tracking needs to be updated on every alloc/free call.

- somehow also track how much to free – since we can call

mallocof any size, but no size is specified when we callfree

- somehow also track how much to free – since we can call

Tracking Allocation Size

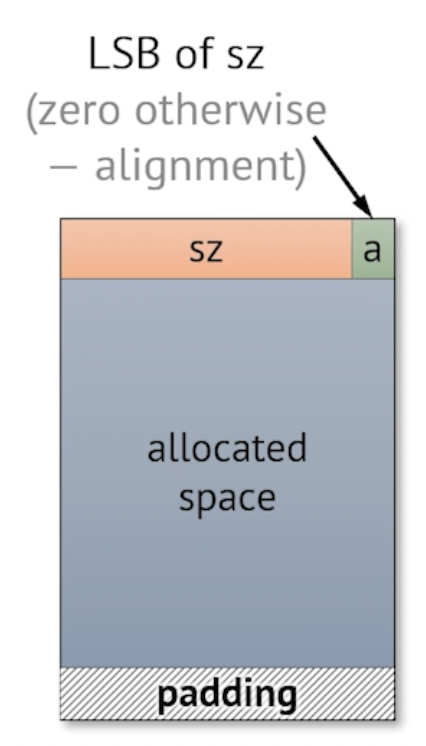

An easy to do is to put such metadata — including the size — as a header in the allocated block — along with the actual allocated data.

- 👍 This is nice because metadata is explict and easy to access; when we call

free, we know exactly how much memory to free. - 👎 However, because the information is stored in the blocks itself, searching for a size globally isn’t easy

- 👎 Takes up heap space for the header

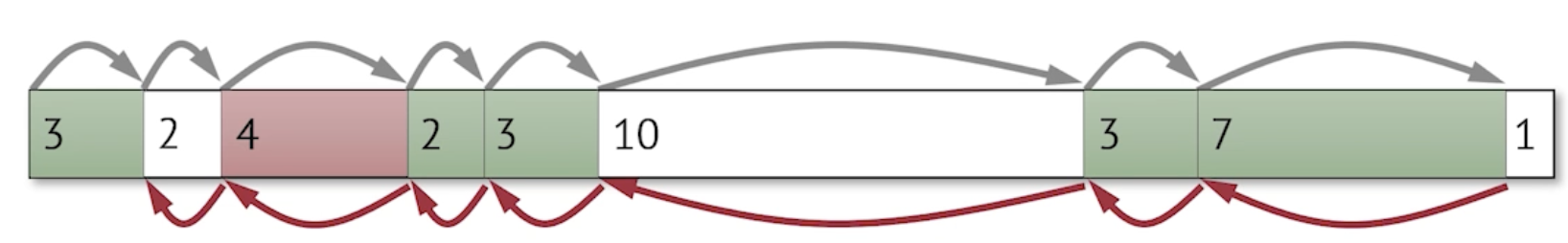

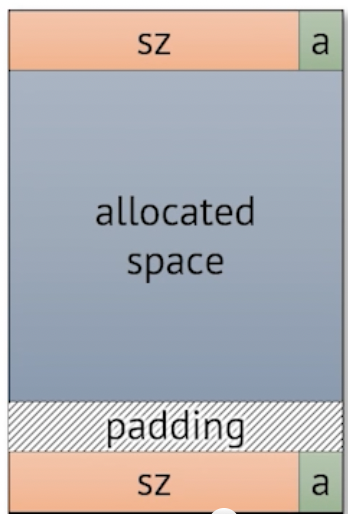

These information can be compacted into this layout:

Where sz is the size of the allocated block, and a is a bit indicating if this is allocated or not.

Tracking Free Space

We want to track where and how much free space there is in the heap.

Implicit Free List

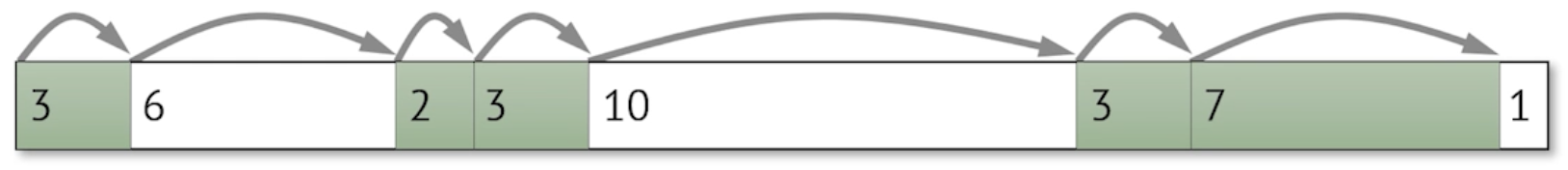

One thing we might do is to list all of allocated AND unallocated blocks by size. Once we know the size, we can implicitly determine where the free locations are.

While this is ssimple, we have to look throught the entire heap to find where free spaces are 😔.

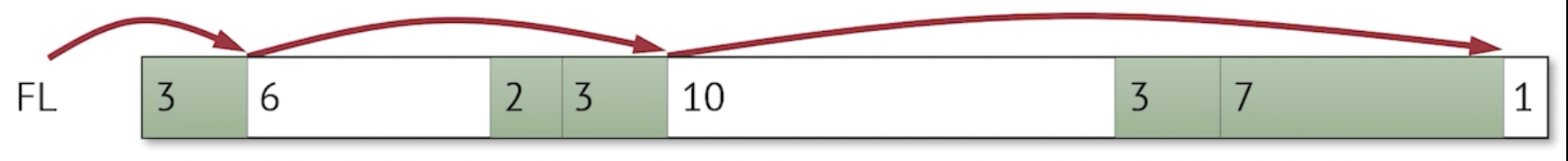

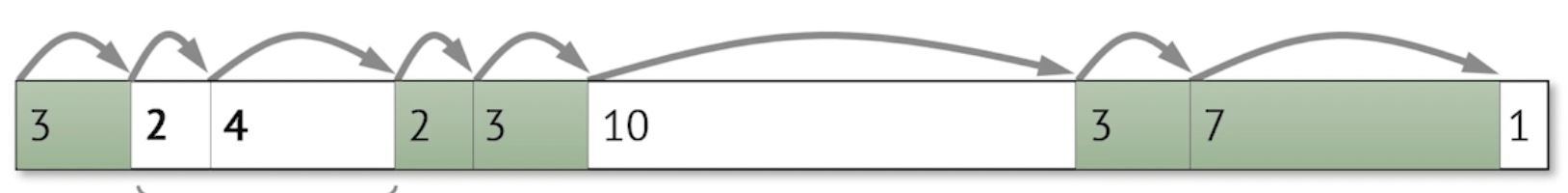

Explicit Free List

Since no program/user is using the unallocated space anyway, we can put a pointer there that points to the next free block. Then we have a linked-list that chains all the free spaces together.

In this example, FL is a pointer to the next free block.

While this is explicit, freeing memory is more complicated since now we have pointers pointing back and forth — and a more complicated operation is required if we want to merge two adjascent free blocks.

Finding Free Space

First Fit

Of course, the simplest way to find free space is to start from the start of the heap and find the next free block that is big enough for allocation.

- But it takes long time to allocate (as it has to potentially look through the entire heap)

- Fragmentation (when the free block size is not big enough).

Next Fit

Instead of starting at the beginning of the heap, start at where last allocation occured. Since we can assume (most of the time) if there were a free block it would’ve been taken during previous allocation.

- Faster allocation time

- Possibly worse fragmentation

Best™ Fit — Minimizes Wasted Space

There are many implemenations that uses tables to track. But allocation time is longer due to look up.

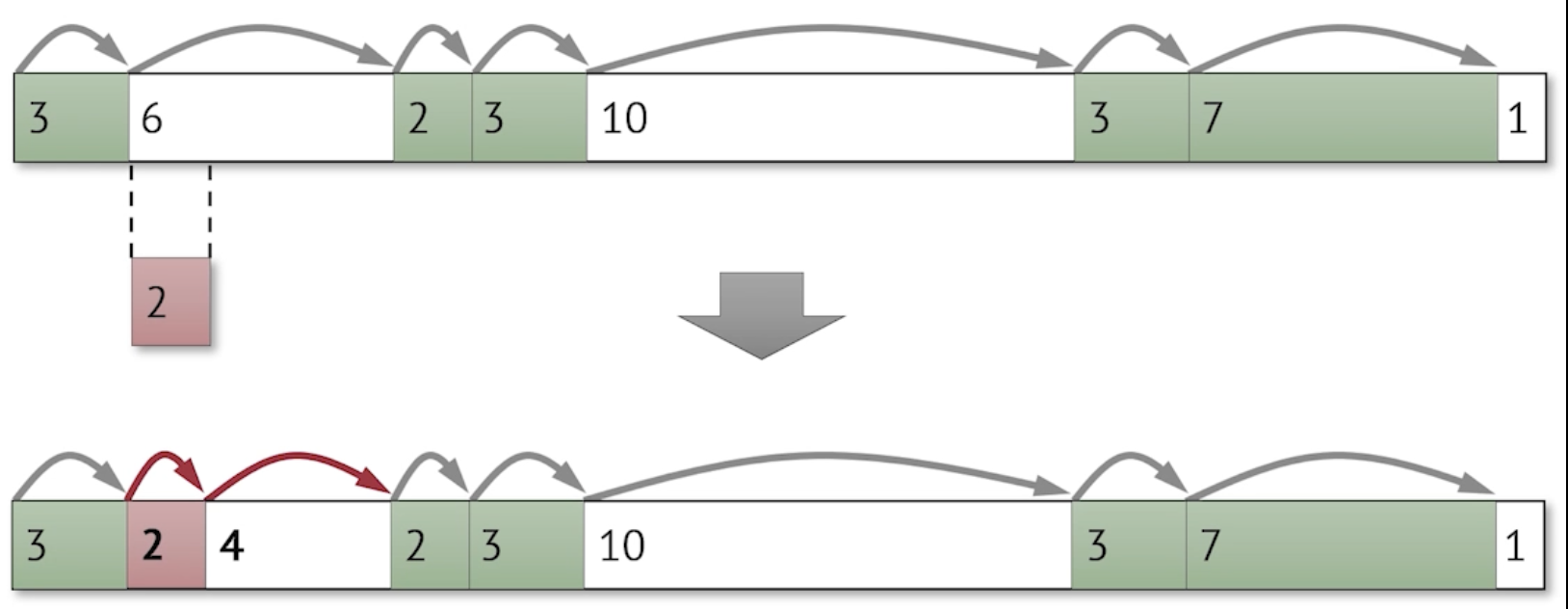

Block Splitting

Once we have a free block, we need to split the free block to accomendate just for the allocation size.

Freeing Memory

Freeing a block seems straightforward: simply find the block address via pointers, then set the allocation flag (a bit) to false – which makes the block as free space available for future allocations.

The problem is that creates fragmentation:

For example if we were to now free the size 2 block from previous section, notice that instead of having one free space of size 6, we have two free space, sized 2 and 4 respectively.

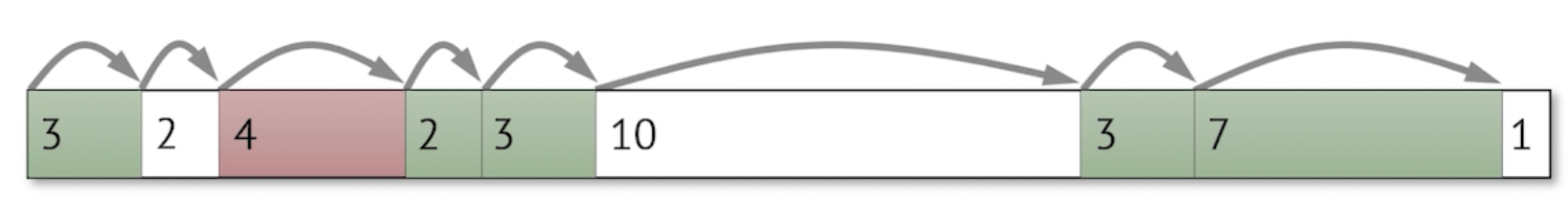

Coalescing Deallocated Blocks

We need to coalesce these free blocks during deallocation to mitigate fragmentation:

- Check if the next block (to the block we’re currently deallocating) is a free block

- If it is, we can merge it

What if the previous block was free? Given this example:

Using our previous method won’t work and will still create fragmentation. We also can’t trivially check previous block since we don’t know where the header is for previous block – thus we cannot find the size.

To fix this, we use boundary tags – which is a bidirectional implicit list that also links to previous blocks. Our new layout for a block is:

Where second set of sz and a is for the reverse direction. This ultimately allows us to have bidirectional traversal in the heap.