Week 1

Updated 2022-01-11

Original slides/talk from Mieszko Lis.

How Software Interact with Hardware System?

Let’s start with a hello-world type program written in ARM assembly:

.text

.global_start

_start:

mov x8, 64

mov x0, 1

adr x1, txt

mov x2, len

svc 0

mov x8, 93

mov x0, 42,

svc 0

txt: .ascii "hello world!\n"

len = . - txt

Note on Syscalls

- The user programs doesn’t have permission to write to the screen and instead have to rely on the kernel via syscall to perform things like accessing to the hardware to the screen

- The mov instructions move values into registers. Here the specific registers are used as “arguments” to the syscall.

- For example,

mov rax, 1is a syscall command for write, andmov rax, 60is the syscall for kill the program.

A Note on Dynamic Dispatching

Consider the following C++ code:

#include <iostream>

struct Super {

void foo() { std::cout << "Super::foo()\n"; }

virtual void bar() { std::cout << "Super::bar()\n"; }

}

struct Sub : Super {

void foo() { std::cout << "Sub::foo()\n"; }

void bar() { std::cout << "Sub::bar()\n"; }

}

int main() {

Super *obj = new Sub();

obj->foo();

obj->bar();

}

Note:

- We have a super class and a sub class that derives from the super class. Note that the bar() function in the super class is virtual but foo() is not.

- The main function createsa. sub-type and stores it in a pointer, but the pointer is declared as a super type.

- Inside the main function, we call the function of the sub-type.

The question is, what are we going to see. What we actually see is:

Super::foo()

Sub::bar()

This is the difference between static and dynamic dispatch. For bar() function it has to look up which method it’s actually referring to – thus has to be dynamically dispatched (as it can only be known at runtime). Whereas foo() is statically dispatched (from compile-time).

ISA

From the assembly code above, clearly this is a language that has some level of abstraction. The instruction set architecture (ISA) helps define this abstraction.

The instruction is a set of instructions the CPU/processor runs on. There are mainly three components:

- Processor State

- Register-Register Instructions such as computation (add, multiply, etc)

- Register-Memory Instructions

Processor State

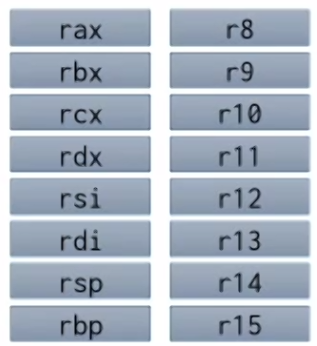

The processor state can be described by its register values. In a CPU there are usually general-purpose registers used to store things. They are architecturally visible – i.e. can be used in programming.

There are also special registers:

- Flags: stores status or outputs from ALUs (e.g. is the comparison equal, is it less than 0, etc.)

- Program counter (PC) or instruction pointer (IP): this points to the instruction to be executed

There are also vector and floating-point registers on modern CPUs that are more optimized to do math quickly, as well as control registers that controls CPU configurations such as going to sleep, address-translation, etc.

In ARMv8 (Aarch64) there is also the stack pointer register (xzr/sp) but it’s not used like a regular register. If attempted to be read, the hardware will intercept and returns a 0.

Additionally there are other registers that may or may not be architecturally visible but can be used for useful things such as performance measuring, sleep, clocks, etc.

Instructions

Instructions can be thought of state-transitions of processor states. For example, consider an addition instruction in ARM assembly:

add x0, x8, x2, lsl #2

This really means: “x0 ← x8 + (x2 « 2)” which is take the value of x2, and left-shift it by 2 bits (multiply by 4) and addit to x8, then store it in x0, where x0, x2, and x8 are CPU registers.

We also need ways to control how we want to do state-transition, we can do this using comparison and branch instructions. Consider:

cmp x0, x1

beq, SOMEWHERE

Here, we compare if the value of x0 and x1 is the same (beq stands for branch if equal), if it is, then jump to SOMEWHERE (another instruction).

Memory Instructions

Now we know we have some hardware registers and some instructions to do computation on the registers. Typically processors have some large amount of memories connected to it. We often need to load inputs from memory, do some computation, and store it back to the memory. Thus, we have load and store instructions that facilates this.

Consider this load instruction:

ldr x0, [x1]

This loads the address value stored in x1 from memory and puts the result into register x0.

Register vs. Memory

Both register and memory stores data, and they’re both index onto a table (register-file (RF) for registers and memory for memory). So why do we have two types? What are the differences?

While registers sits closer to the processor, has a fast access, but extremely small, the main architectural difference is that register index must be encoded into the instruction. The implication is that: we must know which registers to use statically (during compile). Whereas memory addresses can be computered at runtime.

Memory Consistency Model

Another part of ISA is the memory consistency model. Memory consistency implies that memory instructions are executed consistently. In practice, processors execute instructions out-of-order to be efficient. For example, one instruction might be stalled on something, but the following instruction can be executed, so let it execute first.

The question is, can we reorder load instructions?