W19 Assignment 1

Updated 2019-09-11

1. Angles Big and Small

(a) Imagine that you are at the centre of the Earth, which you can assume to be transparent. Consider two points on the Earth’s surface that are separated by 10 arcseconds. What is the physical distance between the two points?

The physical distance we’re looking for between the two points is the arclength we’re trying to find, where the angle is 10 arcseconds. First, we convert the angle from arcsec to radians:

\[\theta=10{\small\text{arcsec}}\times\frac{1{\small\text{arcmin}}}{60{\small\text{arcsec}}}\times\frac{1{\small\deg}}{60{\small\text{arcmin}}}\times\frac{\pi}{180{\small\deg}}=4.85\times10^{-5}\]Then to find the arc length, we use the radius of Earth, which is $R_\oplus$=6371 km.

\[\begin{aligned} d&=\theta r\\ &=\theta R_\oplus\\ &=(4.85\times10^{-5})(6371\text{ km})\\ &=\boxed{0.309\text{ km}} \end{aligned}\]Therefore the distance between the two points is 0.309 km or 308.8 m.

(b) How many square degrees are on the full celestial sphere?

The full celestial sphere is a whole sphere with surface area $A=4\pi r^2$. The square angle of a full celestial sphere is simply the area divided by $r^2$ which gives us $\Omega=4\pi$ steradians.

To convert to square degrees, we use the conversion factor to convert from radians to degrees except we need to square the conversion factor because we’re working with two-dimensional units.

\[\Omega_{\deg}=\Omega\times\left(\frac{180\deg}{\pi}\right)^2\]Plugging in the numbers:

\[\Omega_{\deg}={4\pi\cdot180\over\pi}=\boxed{720\deg^2}\]The solid degrees that covers the full celestial sphere is 720 square degrees.

(c) You have a telescope with a CCD detector that has a square field of view of 4 square arcminutes. How many pointings of the telescope will be needed to cover an area of 6 degrees by 10 degrees?

Assume that we’re looking at the celestial sphere.

Assume that our CCD detector is a square sensor such that the field of view of 4 square arcminutes is 2 arcminutes for horizontal and vertical field of view.

Then we convert 2 arcminutes to degrees:

\[2\small{\text{arcmin}}\times\frac{1\deg}{60\small{\text{arcmin}}}=0.0\bar 3 \deg\]That means we for each frame, we can cover 0.03 degrees by 0.03 degrees. Which means:

\[\frac{6\deg}{0.0333\deg}=180\\ \frac{10\deg}{0.0333\deg}=300\]It takes 180 and 300 pointings respectively to cover 6 degrees by 10 degrees area. Therefore, the total number of pointings required is

\[180\times300=\boxed{54,000}\]We need 54,000 pointings to cover an area of 6 degrees by 10 degrees.

2. Solar System Basics

(a) The observed orbital synodic periods of Venus and Mars and 583.9 days and 779.9 days, respectively. Calculate their sidereal periods.

Assume 1 year is exactly 365.25 days. Then Venus has an orbital synodic period of 1.5986 years, and Mars has an orbital synodic period of 2.1338 years. Synodic means that this is the time interval for the planet to repeat a configuration with respect to Earth.

To calculate the sidereal period, we use the relationship \(\frac{1}{P_\text{syn}}=\frac{1}{P_\text{inner}}-\frac{1}{P_\text{outer}}\)

Venus is an inferior planet. So we’re solving for the “inner” sidereal period; the “outer” sidereal period is Earth’s so it’s simply 1.

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{1.5986\text{ yr}}&=\frac{1}{P_\text{inner}}-1\\ P_\text{inner}&=\left(\frac{1}{1.5986\text{ yr}}+1\right)^{-1}\\ &=\boxed{0.6255 \text{ yr}} \end{aligned}\]Mars is a superior planet. So we are solving for the “outer” sidereal period. Identical procedure:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{2.1338\text{ yr}}&=1-\frac{1}{P_\text{outer}}\\ P_\text{outer}&=\left(1-\frac{1}{2.1338\text{ yr}}\right)^{-1}\\ &=\boxed{1.882 \text{ yr}} \end{aligned}\]The sidereal orbital period of Venus and Mars respectively is 0.6255 years or 228.5 days, and 1.882 years or 687.4 days.

(b) Which of the superior planets has the shortest synodic period, and why?

Using the relationship between sidereal and synodic period from above, and simplifying for superior planets, we get

\[P_{\text{syn}_\text{superior}}=\frac{P_\text{outer}}{P_\text{outer}-1}\]To obtain the shortest synodic period, There must be a great difference in sidereal period of Earth and the superior planet. In other words, in this case, we’re look for a planet with the longest sidereal period, or the planet that orbits farthest away from center.

At the time of writing, the superior planet that has the shortest synodic period is Neptune.

(c) A certain asteroid is 1 au from the Sun at perihelion and 5 au from the Sun at aphelion. Find the semi-major axis, eccentricity, and semi-minor axis of its orbit. Include a sketch of the geometry.

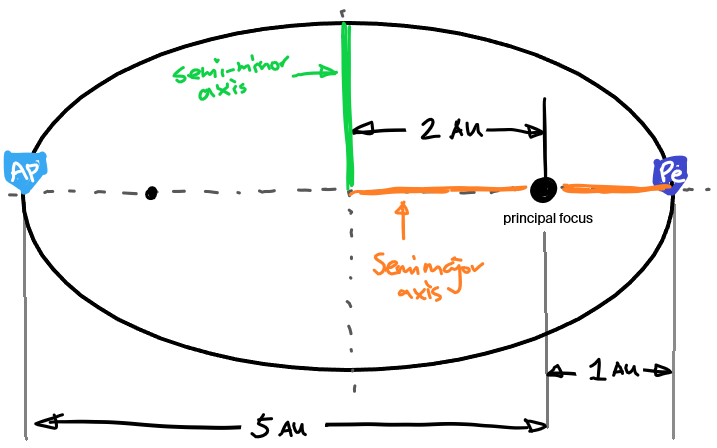

First, the sketch of the geometry:

The perihelion and aphelion (as seen from the drawing) makes up the major axis. Therefore the semimajor axis is given by: \(a=\frac{1\text{AU}+5\text{AU}}{2}=\boxed{3\text{AU}}\) The geometric center is therefore 3AU from both perihelion and aphelion. The distance from one of the foci to the geometric center is given by $ae=2$AU. This distance is determined by subtraction of perihelion as seen in the drawing.

Therefore the eccentricity is: \(e=\frac{2\text{AU}}{3\text{AU}}=\boxed{2/3}\)

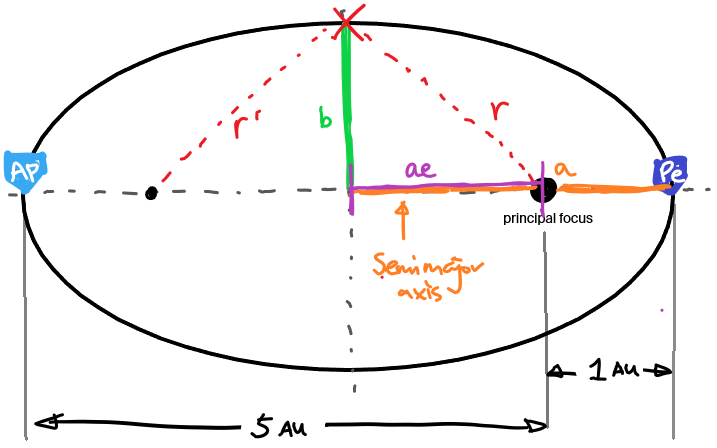

Now we assume a point on the ellipse such that the distance to one focus is the same as to the other focus ($r=r’$).

Then we can make a right-angle triangle and apply the Pythagoras theorem to find the semi-minor axis $b$. In particular, we know that $r=r’$ and that the definition of the ellipse is $r+r’=2a$ which leads to $r=r’=a$.

Applying the Pythagorean theorem with the right triangle: \(b^2+(ae)^2=r^2\) Substitute the variables and then rearrange we can calculate the semi-minor axis $b$: \(\begin{aligned} b^2&=a^2(1-e^2)\\ b&=\sqrt{a^2(1-e^2)}\\ &=\sqrt{(3)^2\left(1-\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^2\right)}\\ &=\sqrt{5}\\ &=\boxed{2.236\text{AU}} \end{aligned}\) The geometry of the asteroid’s orbit has semimajor axis of 3AU, eccentricity of ⅔ or 0.667, and semi-minor axis of 2.236AU.

3. Calculus Refresher

A simple model of a planetary atmosphere has the number density $n$ decreasing roughly exponentially with height $z$ above the planet’s surface: $n(z)=n_0e^{-z/H_p}$, where $n_0$ is the number density at the surface of the planet, and $H_p$ is is the pressure scale height. At the surface of the Earth, the number density for nitrogen is $n_0=2\times 10^{25} \text{m}^{-3}$ and the scale height for is about $H_p=8.7$ km. The model is valid up to about 90 km. Compute the number of nitrogen molecules in the Earth’s atmosphere. You will have to make at least one important approximation in order to do this; explain clearly what you have done.

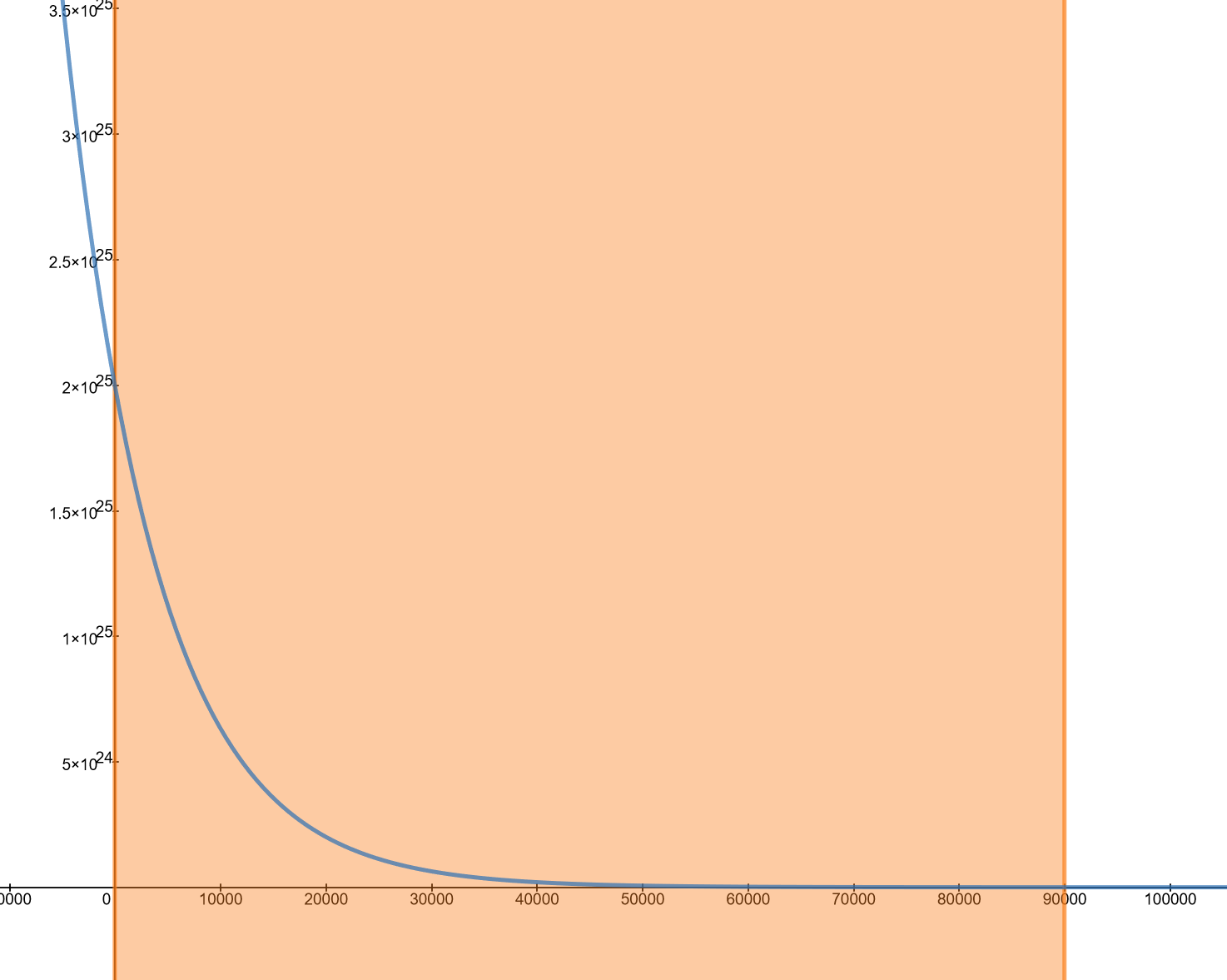

First, let’s graph the density function of Nitrogen from sea level (z=0) to z=90 km:

Approximation #1

Notice that even though the exponential decay of number of particles is significant at the altitude of 90 km, there is still a significant number of nitrogen particles in magnitude of 6.43×1020 per meter cubed. We can make an approximation that the function $n(z)$ is piecewise such that for $z>90$ km, $n(z)=0$.

Approximation #2

We approximate that the planet is a completely smooth sphere such that the density is uniform everywhere.

Integration Function

The function for total number of particles is an integration of a multiplication of density function and volume.

\[\int_0^{90,000}n(z)A(z)\mathrm dz\]Where $n(z)$ is the density function of Nitrogen as previously defined. Function $A(z)$ is surface area of the atmosphere for a specific $z$ height. Both $A(z)\mathrm dz$ will give us the volume of infinitesimal slice of the atmosphere. The area function is given by the formula of the surface area of a sphere plus the altitude $z$:

\[A(z)=4\pi (R_\oplus+z)^2\]Computing the Integral

\[\begin{aligned} N&=\int n(z)A(z)\mathrm dz\\ &=4\pi n_0 \int e^\frac{-z}{H_p}(R_\oplus+z)^2 \mathrm dz \end{aligned}\]This is a very complicated function to integrate. So let’s do some digging into whether if this is necessary (See next section).

Approximation #3

The lower bound of the surface area is at sea-level, where z=0, then $A(0)$=5.10×108 km2. The upper bound is at z=90km, and $A(90\text{km})$=5.24×108 km2, which is less than 3% difference.

Knowing that because Earth’s radius is so large compared to the thickness of the atmosphere we’re considering, we can approximate Earth’s atmosphere as a flat sheet, by “unwrapping” the spherical shell into a flat disk with top area of $4\pi R_\oplus^2$ and 90km thick.

Now the modified function to integrate is as follows. The two equations are for lower and upper bound of number of nitrogen particles, respectively.

\[N_\text{lower bound}=4\pi R_\oplus^2 n_0 \int e^{-\frac{z}{H_p}} \mathrm dz\\ N_\text{upper bound}=4\pi (R_\oplus+90,000)^2 n_0 \int e^{-\frac{z}{H_p}} \mathrm dz\]But because of the exponential falloff of the number of particles as we move away from Earth’s surface, the lower bound approximation is more accurate. Ergo we will just calculate the lower bound.

Computing the Definite Integral

Let’s do the integration first.

\[\begin{aligned} \int_0^{90,000} e^{-\frac{z}{H_p}}\mathrm dz &=\left[-H_p e^{-\frac{z}{H_p}}\right]^{z=90,000}_{z=0}\\ &=H_p \left( 1-e^{-\frac{90,000}{H_p}} \right)\\ &=8,700 \left( 1-e^{-\frac{90,000}{8,700}} \right)\\ &=8,699.72\text{m} \end{aligned}\]Now we multiply the rest:

\[\begin{aligned} 4\pi R_\oplus^2 n_0 \int e^{-\frac{z}{H_p}} \mathrm dz &=4\pi R_\oplus^2 n_0(8699.72)\\ &=\boxed{8.875\times10^{43}} \end{aligned}\]Using meter as standard unit for all calculations, we get the final answer of 8.875×1043 particles.